A projector or image projector is an optical device that projects an image (or moving images) onto a surface, commonly a projection screen. Most projectors create an image by shining a light through a small transparent lens, but some newer types of projectors can project the image directly, by using lasers. A virtual retinal display, or retinal projector, is a projector that projects an image directly on the retina instead of using an external projection screen.

The most common type of projector used today is called a video projector. Video projectors are digital replacements for earlier types of projectors such as slide projectors and overhead projectors. These earlier types of projectors were mostly replaced with digital video projectors throughout the 1990s and early 2000s,[1] but old analog projectors are still used at some places. The newest types of projectors are handheld projectors that use lasers or LEDs to project images.

Movie theaters used a type of projector called a movie projector, nowadays mostly replaced with digital cinema video projectors.

Different projector types

[edit]

Projectors can be roughly divided into three categories, based on the type of input. Some of the listed projectors were capable of projecting several types of input. For instance: video projectors were basically developed for the projection of prerecorded moving images, but are regularly used for still images in PowerPoint presentations and can easily be connected to a video camera for real-time input. The magic lantern is best known for the projection of still images, but was capable of projecting moving images from mechanical slides since its invention and was probably at its peak of popularity when used in phantasmagoria shows to project moving images of ghosts.

Real-time

[edit]

Still images

[edit]

- Slide projectorLarge-format slide projector

- Magic lantern

- Magic mirror

- Steganographic mirror (see below for details)

- Enlarger (not for direct viewing, but for the production of photographic prints)

Moving images

[edit]

- Movie projector

- Mini portable home theatres projector[2]

- Video projector

- Handheld projector

- Virtual retinal display

- Revolving lanterns (see below for details)

History

[edit]

There probably existed quite a few other types of projectors than the examples described below, but evidence is scarce and reports are often unclear about their nature. Spectators did not always provide the details needed to differentiate between for instance a shadow play and a lantern projection. Many did not understand the nature of what they had seen and few had ever seen other comparable media. Projections were often presented or perceived as magic or even as religious experiences, with most projectionists unwilling to share their secrets. Joseph Needham sums up some possible projection examples from China in his 1962 book series Science and Civilization in China[3]

Prehistory to 1100

[edit]

Shadow play

[edit]

Main article: shadow play

The earliest projection of images was most likely done in primitive shadowgraphy dating back to prehistory. Shadow play usually does not involve a projection device, but can be seen as a first step in the development of projectors. It evolved into more refined forms of shadow puppetry in Asia, where it has a long history in Indonesia (records relating to Wayang since 840 CE), Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, China (records since around 1000 CE), India and Nepal.

Camera obscura

[edit]

Main articles: Camera obscura and Pinhole camera

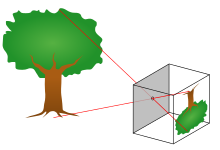

Projectors share a common history with cameras in the camera obscura. Camera obscura (Latin for “dark room”) is the natural optical phenomenon that occurs when an image of a scene at the other side of a screen (or for instance a wall) is projected through a small hole in that screen to form an inverted image (left to right and upside down) on a surface opposite to the opening. The oldest known record of this principle is a description by Han Chinese philosopher Mozi (ca. 470 to ca. 391 BC). Mozi correctly asserted that the camera obscura image is inverted because light travels in straight lines.[citation needed]

In the early 11th century, Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) described experiments with light through a small opening in a darkened room and realized that a smaller hole provided a sharper image.[citation needed]

Chinese magic mirrors

[edit]

The oldest known objects that can project images are Chinese magic mirrors. The origins of these mirrors have been traced back to the Chinese Han dynasty (206 BC – 24 AD)[4] and are also found in Japan. The mirrors were cast in bronze with a pattern embossed at the back and a mercury amalgam laid over the polished front. The pattern on the back of the mirror is seen in a projection when light is reflected from the polished front onto a wall or other surface. No trace of the pattern can be discerned on the reflecting surface with the naked eye, but minute undulations on the surface are introduced during the manufacturing process and cause the reflected rays of light to form the pattern.[5] It is very likely that the practice of image projection via drawings or text on the surface of mirrors predates the very refined ancient art of the magic mirrors, but no evidence seems to be available.

Revolving lanterns

[edit]

Revolving lanterns have been known in China as “trotting horse lamps” [走馬燈] since before 1000 CE. A trotting horse lamp is a hexagonal, cubical or round lantern which on the inside has cut-out silhouettes attached to a shaft with a paper vane impeller on top, rotated by heated air rising from a lamp. The silhouettes are projected on the thin paper sides of the lantern and appear to chase each other. Some versions showed some extra motion in the heads, feet and/or hands of figures by connecting them with a fine iron wire to an extra inner layer that would be triggered by a transversely connected iron wire.[6] The lamp would typically show images of horses and horse-riders.

In France, similar lanterns were known as “lanterne vive” (bright or living lantern) in medieval times. and as “lanterne tournante” since the 18th century. An early variation was described in 1584 by Jean Prevost in his small octavo book La Premiere partie des subtiles et plaisantes inventions. In his “lanterne”, cut-out figures of a small army were placed on a wooden platform rotated by a cardboard propeller above a candle. The figures cast their shadows on translucent, oiled paper on the outside of the lantern. He suggested to take special care that the figures look lively: with horses raising their front legs as if they were jumping and soldiers with drawn swords, a dog chasing a hare, etcetera. According to Prevost barbers were skilled in this art and it was common to see these night lanterns in their shop windows.[7]

A more common version had the figures, usually representing grotesque or devilish creatures, painted on a transparent strip. The strip was rotated inside a cylinder by a tin impeller above a candle. The cylinder could be made of paper or of sheet metal perforated with decorative patterns. Around 1608 Mathurin Régnier mentioned the device in his Satire XI as something used by a patissier to amuse children.[8] Régnier compared the mind of an old nagger with the lantern’s effect of birds, monkeys, elephants, dogs, cats, hares, foxes and many strange beasts chasing each other.[9]

John Locke (1632–1704) referred to a similar device when wondering if ideas are formed in the human mind at regular intervals,”not much unlike the images in the inside of a lantern, turned round by the heat of a candle.” Related constructions were commonly used as Christmas decorations in England [10] and parts of Europe. A still relatively common type of rotating device that is closely related does not really involve light and shadows, but it simply uses candles and an impeller to rotate a ring with tiny figurines standing on top.

Many modern electric versions of this type of lantern use all kinds of colorful transparent cellophane figures which are projected across the walls, especially popular for nurseries.

1100 to 1500

[edit]

Concave mirrors

[edit]

The inverted real image of an object reflected by a concave mirror can appear at the focal point in front of the mirror.[11] In a construction with an object at the bottom of two opposing concave mirrors (parabolic reflectors) on top of each other, the top one with an opening in its center, the reflected image can appear at the opening as a very convincing 3D optical illusion.[12]

The earliest description of projection with concave mirrors has been traced back to a text by French author Jean de Meun in his part of Roman de la Rose (circa 1275).[13] A theory known as the Hockney-Falco thesis claims that artists used either concave mirrors or refractive lenses to project images onto their canvas/board as a drawing/painting aid as early as circa 1430.[14]

It has also been thought that some encounters with spirits or gods since antiquity may have been conjured up with (concave) mirrors.[15]

Fontana’s lantern

[edit]

Around 1420 the Venetian scholar and engineer Giovanni Fontana included a drawing of a person with a lantern projecting an image of a demon in his book about mechanical instruments “Bellicorum Instrumentorum Liber”.[16] The Latin text “Apparentia nocturna ad terrorem videntium” (Nocturnal appearance to frighten spectators)” clarifies its purpose, but the meaning of the undecipherable other lines is unclear. The lantern seems to simply have the light of an oil lamp or candle go through a transparent cylindrical case on which the figure is drawn to project the larger image, so it probably could not project an image as clearly defined as Fontana’s drawing suggests.

Possible 15th century image projector

[edit]

In 1437 Italian humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher and cryptographer Leon Battista Alberti is thought to have possibly projected painted pictures from a small closed box with a small hole, but it is unclear whether this actually was a projector or rather a type of show box with transparent pictures illuminated from behind and viewed through the hole.[17]

1500 to 1700

[edit]

16th to early 17th century

[edit]

Leonardo da Vinci is thought to have had a projecting lantern – with a condensing lens, candle and chimney – based on a small sketch from around 1515.[18]

In his Three Books of Occult Philosophy (1531–1533) Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa claimed that it was possible to project “images artificially painted, or written letters” onto the surface of the Moon with the means of moonbeams and their “resemblances being multiplied in the air”. Pythagoras would have often performed this trick.[19]

In 1589 Giambattista della Porta published about the ancient art of projecting mirror writing in his book Magia Naturalis.[20][21]

Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel, who is a likely inventor of the microscope, is thought to have had some kind of projector that he used in magical performances. In a 1608 letter he described the many marvelous transformations he performed and the apparitions that he summoned by the means of his new invention based on optics. It included giants that rose from the earth and moved all their limbs very lifelike.[22] The letter was found in the papers of his friend Constantijn Huygens, father of the likely inventor of the magic lantern Christiaan Huygens.

Helioscope

[edit]

In 1612 Italian mathematician Benedetto Castelli wrote to his mentor, the Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher and mathematician Galileo Galilei about projecting images of the sun through a telescope (invented in 1608) to study the recently discovered sunspots. Galilei wrote about Castelli’s technique to the German Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer Christoph Scheiner.[23]

From 1612 to at least 1630 Christoph Scheiner would keep on studying sunspots and constructing new telescopic solar projection systems. He called these “Heliotropii Telioscopici”, later contracted to helioscope.[23]

Steganographic mirror

[edit]

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher‘s book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae included a description of his invention, the steganographic mirror: a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.[24] Kircher also suggested projecting live flies and shadow puppets from the surface of the mirror.[25] The book was quite influential and inspired many scholars, probably including Christiaan Huygens who would invent the magic lantern. Kircher was often credited as the inventor of the magic lantern, although in his 1671 edition of Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae Kircher himself credited Danish mathematician Thomas Rasmussen Walgensten for the magic lantern, which Kircher saw as a further development of his own projection system.[26][27]

Although Athanasius Kircher claimed the Steganographic mirror as his own invention and wrote not to have read about anything like it,[27] it has been suggested that Rembrandt’s 1635 painting of “Belshazzar’s Feast” depicts a steganographic mirror projection with God’s hand writing Hebrew letters on a dusty mirror’s surface.[28]

In 1654 Belgian Jesuit mathematician André Tacquet used Kircher’s technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionary Martino Martini.[29] It is sometimes reported that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern which he might have imported from China, but there’s no evidence that anything other than Kircher’s technique was used.

Magic lantern

[edit]

Main article: Magic lantern

By 1659 Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens had developed the magic lantern, which used a concave mirror to reflect and direct as much of the light of a lamp as possible through a small sheet of glass on which was the image to be projected, and onward into a focusing lens at the front of the apparatus to project the image onto a wall or screen (Huygens apparatus actually used two additional lenses). He did not publish nor publicly demonstrate his invention as he thought it was too frivolous.

The magic lantern became a very popular medium for entertainment and educational purposes in the 18th and 19th century. This popularity waned after the introduction of cinema in the 1890s. The magic lantern remained a common medium until slide projectors came into widespread use during the 1950s.

1700 to 1900

[edit]

Solar microscope

[edit]

A few years before his death in 1736 Polish-German-Dutch physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit reportedly constructed a solar microscope, which was a combination of the compound microscope with camera obscura projection. It needed bright sunlight as a light source to project a clear magnified image of transparent objects. Fahrenheit’s instrument may have been seen by German physician Johann Nathanael Lieberkühn who introduced the instrument in England, where optician John Cuff improved it with a stationary optical tube and an adjustable mirror.[30] In 1774 English instrument maker Benjamin Martin introduced his “Opake Solar Microscope” for the enlarged projection of opaque objects. He claimed:

The Opake Microsc[o]pe, not only magnifies the natural Appearance or Size of Objects of every Sort, but at the ſame time throws ſuch a Quantity of Solar Rays upon them, as to make all their Colours appear vaſtly more vivid and ſtrong than to the naked Eye; and their Parts ſo expanded and diſtinct upon a fixed Screen, that they are not only viewed with the utmoſt Pleaſure, but may be drawn with the greateſt Eaſe by any ingenious Hand.”[31]

The solar microscope,[32] was employed in experiments with photosensitive silver nitrate by Thomas Wedgwood in collaboration with Humphry Davy in making the first, but impermanent, photographic enlargements. Their discoveries, regarded as the earliest deliberate and successful form of photography, were published in June 1802 by Davy in his An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq. With Observations by H. Davy in the first issue of the Journals of the Royal Institution of Great Britain.[33][34]

Opaque projectors

[edit]

Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician and engineer Leonhard Euler demonstrated an opaque projector, now commonly known as an episcope, around 1756. It could project a clear image of opaque images and (small) objects.[35]

French scientist Jacques Charles is thought to have invented the similar “megascope” in 1780. He used it for his lectures.[36] Around 1872 Henry Morton used an opaque projector in demonstrations for huge audiences, for example in the Philadelphia Opera House which could seat 3500 people. His machine did not use a condenser or reflector, but used an oxyhydrogen lamp close to the object in order to project huge clear images.[37]

Solar camera

[edit]

See main article: Solar camera

Known equally, though later, as a solar enlarger, the solar camera is a photographic application of the solar microscope and an ancestor of the darkroom enlarger, and was used, mostly by portrait photographers and as an aid to portrait artists, in the mid-to-late 19th century[38] to make photographic enlargements from negatives using the Sun as a light source powerful enough to expose the then available low-sensitivity photographic materials. It was superseded in the 1880s when other light sources, including the incandescent bulb, were developed for the darkroom enlarger and materials became ever more photo-sensitive.[32][39]

20th century to present day

[edit]

In the early and middle parts of the 20th century, low-cost opaque projectors were produced and marketed as a toy for children. The light source in early opaque projectors was often limelight, with incandescent light bulbs and halogen lamps taking over later. Episcopes are still marketed as artists’ enlargement tools to allow images to be traced on surfaces such as prepared canvas.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, overhead projectors began to be widely used in schools and businesses. The first overhead projector was used for police identification work.[citation needed] It used a celluloid roll over a 9-inch stage allowing facial characteristics to be rolled across the stage. The United States military in 1940 was the first to use it in quantity for training.[40][41][42][43]

From the 1950s to the 1990s slide projectors for 35 mm photographic positive film slides were common for presentations and as a form of entertainment; family members and friends would occasionally gather to view slideshows, typically of vacation travels.[44]

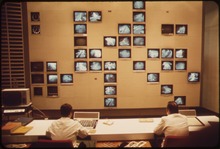

Complex Multi-image shows of the 1970s to 1990s, purposed usually for marketing, promotion or community service or artistic displays, used 35mm and 46mm transparency slides (diapositives) projected by single or multiple slide projectors onto one or more screens in synchronization with an audio voice-over and/or music track controlled by a pulsed-signal tape or cassette.[45] Multi-image productions are also known as multi-image slide presentations, slide shows and diaporamas and are a specific form of multimedia or audio-visual production.

Digital cameras had become commercialised by 1990, and in 1997 Microsoft PowerPoint was updated to include image files,[46] accelerating the transition from 35 mm slides to digital images, and thus digital projectors, in pedagogy and training.[47] Production of all Kodak Carousel slide projectors ceased in 2004,[48] and in 2009 manufacture and processing of Kodachrome film was discontinued.[49]

Developments since 2020

[edit]

Since 2020, projector technology has advanced significantly:

- Laser light sources have become mainstream, offering longer lifespans, higher brightness, and wider color gamuts.

- 4K resolution is now standard in home theaters, while 8K resolution is emerging in high-end markets.

- Smart projectors integrate operating systems, streaming apps, and voice assistants, enhancing user convenience.

- Ultra Short Throw (UST) technology enables large-screen projection in limited spaces.

- Improvements in HDR and wide color gamut technologies have significantly enhanced image quality.

- Portable projectors have seen advancements in size, battery life, and features like auto-focus and keystone correction.

- Gaming projectors focus on low input lag and high refresh rates for immersive gaming experiences.

- Environmental and energy-saving technologies are prioritized, with efficient light sources and power-saving modes.

- Projectors are increasingly used in AR and VR applications for education, training, and entertainment.

- AI technology is integrated for features like auto-focus, image optimization, and voice control.

In popular culture

[edit]

In Mad Men‘s first series the final episode presents the protagonist Don Draper’s presentation (via slide projector) of a plan to market the Kodak slide carrier a ‘carousel’.[44]